Observations on Selected Aspects of Liu Kang’s Painting Practice

Article information

Abstract

This article gathers, for the first time, some intriguing technical features of Liu Kang’s painting practice, which spans seven decades. These features encompass retouching, alteration as well as the painting over of rejected compositions and painting on the reverse sides of earlier artworks. As Liu Kang (1 91 1–2004) did not discuss the technical details of his artistic process, an exploration of these aspects of the artist’s expression helps us understand the motivation behind his unconventional decisions. The paint layers were characterised through imaging methods like visible light (VIS), ultraviolet fluorescence (UVF), near-infrared (NIR), reflectance transformation imaging (RTI), digital optical microscopy (DOM) and X-ray radiography (XRR). The technical analyses were additionally supplemented with archival sources. The results showed that some aspects of the artist’s painting practice may distort the provenance of the paintings, impact dating, visual interpretation of his painting technique and style, as well as future conservation and display decisions. The presented case studies discuss the influence of Liu Kang’s unconventional painting approaches on the perception and interpretation of his artworks. Additionally, some hidden alterations and entirely new compositions were revealed for the first time and presented here, adding to growing knowledge about the artist’s painting technique. Moreover, universal aesthetical and ethical considerations were discussed in the context of the conservation and display approach to the artist’s retouching work and double-sided paintings. Besides, this research promotes a need for obtaining a comprehensive understanding of Liu Kang’s painting practice and coherent guidelines to ensure proper presentation of his artworks and to prevent misinterpretation of his technique and artistic outcomes.

1. INTRODUCTION

Liu Kang (1911–2004) was a Chinese emigree to Singapore who gained art education in two major East and West art centres – Shanghai and Paris (Chow, 1996; 2000; Hoe, 1955). He became widely known in Southeast Asia for his contribution to the Nanyang style – a painting concept practised in Singapore from the late 1940s to the 1960s (Sabapathy, 1982). The style drew from two opposite artistic sources – the School of Paris and Chinese painting traditions. His amalgamation of different techniques and aesthetics was applied to depicting Southeast Asian or local subject matter (Ong, 2012; Rawanchaikul, 2011; Sabapathy, 1987; Sullivan, 1957). The incorporation of stylistic elements of the batik technique was an additional feature of the style (Chow, 1996; Lizun et al., 2022a; Ong et al., 2011). Besides having a vital role in developing the Nanyang style, Liu Kang repeatedly departed from his established artistic way to search for new sources of inspiration and to experiment with various forms of expression (Liu, 1997). Moreover, his frequent re-evaluations of old themes resulted in the creation of his iconic series of Huangshan and Guilin mountains as well as studies of nudes. Additionally, the artist’s painting practice is characterised by various unconventional technical solutions. For instance, the alteration of completed compositions is a frequently observed feature of the paint layers (Lizun, 2021a; Lizun et al., 2022a; Lizun et al., 2022b), even though the artist thoroughly studied the subject matter (Wai Hon, 1997) through intensive sketching and photography prior to the actual painting (Liu, 2002; Yow, 2011). This suggests that the paintings did not always arise in a linear workflow. Besides consisting of compositional and colouristic changes, which were often conducted in distinct stages, his creative process was also shaped by unpredictable emotions. Hence, some of his artistic outcomes remain difficult to interpret (Lizun et al., 2022b). Moreover, the artist’s painting practice was also impacted by financial difficulties or the lack of art materials. Therefore, to continue with his artistic development, he was forced to paint over earlier compositions (Lizun, 2021a; Lizun et al., 2021b; Lizun et al., 2021c; Lizun et al., 2021d).

Despite the fact that Liu Kang was an active art educator and critic (Liu, 2011), he did not publicly share information about his painting materials and techniques, and this provokes questions about how his paintings were made. The unusual features, such as retouching, alteration as well as the painting over of rejected compositions and painting on the reverse sides of earlier compositions, although mentioned in the previous research in the context of his different artistic phases, have never been thoroughly discussed. Hence, this article gathers the findings of earlier analytical campaigns and additional unpublished data in an attempt to gain a deeper understanding of the artist’s creative process and his motivations behind the unconventional technical decisions. Particularly interesting is the impact of his painting practice on provenance studies, dating, aesthetic perception, the interpretation of his techniques, compositions and colour schemes, as well as decisions about conservation and display.

2. MATERIALS

This study focuses on 25 oil paintings on canvas and hardboard by Liu Kang from National Gallery Singapore (NGS) and Liu family collections. The selected paintings were created by the artist during different artistic phases between 1930 and 1999, and hence provide an overview of the artist’s oeuvre. As the artworks from Liu family have remained in their original condition and those from NGS were donated by the artist, the unconventional technical and stylistic features can be attributed to Liu Kang. Hence, this study avoids the misinterpretation that could be caused by the presence of paint features applied by other parties. Table 1 summarises the inventory and technical data of the studied paintings.

3. METHODS

The adopted analytical approach relied on non-invasive imaging techniques to enhance the rendering of the peculiarities of the paint layers and to reveal the presence of the underlying compositions. For consistency with the results obtained in the previous research campaigns, the workflows of the acquisition and processing of the images were identical. In this respect, the technical photography was conducted with a Nikon D850 DSLR modified camera with a sensitivity of 360 – 1100 nm. The camera was equipped with a Nikon AF Micro NIKKOR 60 mm f/2.8D lens. The images were acquired according to the workflow proposed by Cosentino (Cosentino, 2014; 2015; 2016). The X-Rite ColorChecker Passport and the American Institute of Conservation Photo Documentation (AIC PhD) targets were used for camera calibration and colour management of the images. Visible (VIS) and ultraviolet fluorescence (UVF) photography were acquired by mounting on the lens X-Nite CC1 and B+W 415 f ilters. T he n ear-infrared (NIR) photography was acquired with Heliopan RG1000 filter.

The illumination systems for UVF photography consisted of t wo lamps e quipped with e ight 4 0 W 365 n m UV fluorescence tubes. Two 500 W halogen lamps provided the lighting system for VIS and NIR photography. Further processing of the images was conducted using Adobe Photoshop CC according to the standards described by the American Institute of Conservation (Warda et al., 2011).

The texture of the paint layers was studied with reflectance transformation imaging (RTI), following the workflow developed by Cultural Heritage Imaging. The captured images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CC and RTIBuilder. The generated images were interactively viewed using RTIViewer (Schroer et al., 2011; Schroer et al., 2013). Then, digital optical microscopy (DOM) provided insights into the structure of the individual features of the artist’s technique. DOM was conducted using Keyence VHX-6000 with a zoom lens at a magnification range of 20x to 200x. Further verification of the hidden compositions was conducted with NIR and a digital X-ray radiography (XRR) system – Siemens Ysio Max. The instrument utilises a 7 MP resolution detector of dimensions 35 × 43 cm. The X-ray tube operated at 40 kV and 0.5 – 2 mAs. The radiographic images were visualised and processed using iQ-LITE, then exported to Adobe Photoshop CC for final alignment and merging. The results of the imaging techniques were cross-referenced with the artist’s photographs of the paintings and exhibition catalogues to trace the history of the paintings and confirm their condition and further modifications.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1. Retouches

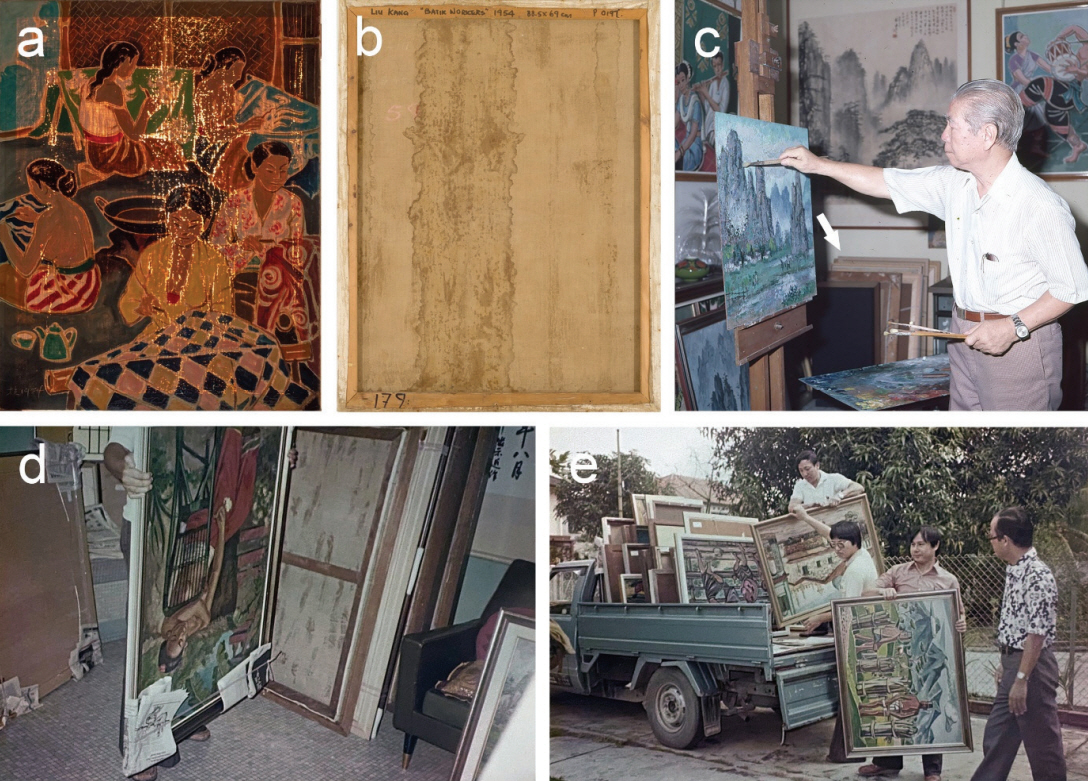

Paradoxically, Liu Kang’s compensation of paint and ground layer losses is a predominant factor impacting the condition of some of his paintings. The probable cause of the initial losses could be linked to distortions of the canvas painting supports caused by the humid tropical climate of Singapore or by direct contact with water (Figure 1a, b). The tight storage space in the artist’s studio (Figure 1c, d) or inadequate handling and transportation conditions (Figure 1e) could also have negatively contributed to the poor condition of the paint layers.

Image of Batik workers by Liu Kang, 1954, oil on canvas, 88.5 × 69 cm (a). The painting was photographed in transmitted VIS to show the losses of the paint and ground layers. The reverse side of the painting shows water marks that could have been responsible for distortions of the canvas and subsequent losses of the ground and paint layer (b). Gift of the artist’s family. Collection of National Gallery Singapore. Archival, undated photographs of Liu Kang’s studio, showing paintings stacked against the wall (c, d). Archival, undated photograph showing loading of Liu Kang’s paintings into the vehicle. Images (c–e) are from Liu Kang family collection. Images courtesy of Liu family.

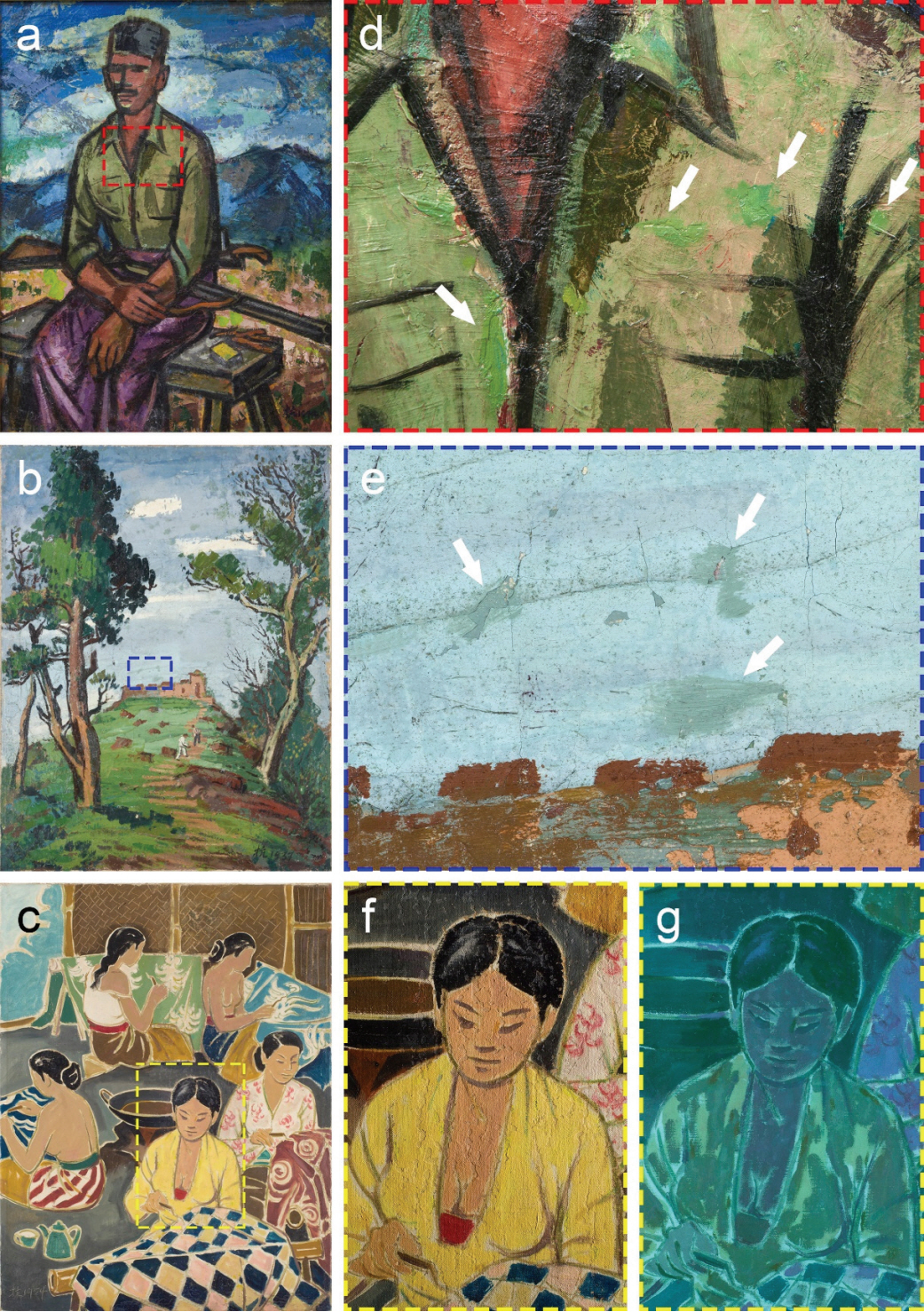

The artist attempted to address the issue of the severe paint losses by liberally retouching the areas of loss and the surrounding original paint. This intervention is easily noticeable by its technical and aesthetic drawbacks. The artist’s failure to use filling material to reconstruct the primer resulted in visible differences between the thickness of the original paint layers and their compensation. Moreover, low-quality colour matchings, executed with oil paints which additionally discoloured over time, as well as their poor application manner, in brush strokes incompatible with the surrounding paint application style, additionally reduce the aesthetic properties of the paintings, as the cases of Malay man (1942), Bathing in the river (1947), Climbing the hill (1948) and Fruit sellers (1969) (Figure 2a, d, b, e). Regarding the extensive paint losses in Batik workers (1954), the artist’s approach involved reworking the affected passages following the original paint scheme, but without infilling (Figure 2c, f, g).

The paintings by Liu Kang: (a) Malay man, 1942, oil on canvas, 94 × 73 cm; (b) Climbing the hill, 1948, oil on canvas, 75 × 61 cm; (c) Batik workers, 1954, oil on canvas, 88.5 × 69 cm. Corresponding details indicate the artist’s retouches (d, e) and reworked passages for compensating the ground and paint losses seen in VIS raking light (f) and UVF (g). Paintings (a-c) are gifts of the artist’s family. Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

Although it remains unknown when, specifically, Liu Kang retouched his paintings, his family recalled that some retouchings were done in the 1980s and 1990s, when he struggled with deteriorating eyesight. The artist mentioned worsening eyesight problems in two interviews in 1981 (Mahbubani, 1981) and 1989: “Before the operations, I was very upset and reluctant to work. […] I was depressed. But after the cornea operations in 1986, I slowly started to paint again. Of course, there is a difference. The colours are different. I used too much blue and green and my children would point it out to me. I can’t paint for periods now. Before, I could paint through the whole day. Now, I get tired. It is a problem” (Sasitharan, 1989). Indeed, the problems with the left eye cornea relapsed, and he lost sight in that eye in 1992 until a successful corneal transplant in 1993. In a 1993 interview, he recalled: “Since I couldn’t see with my left eye, I am painting at much slower pace now. A painting which needed only two to three days to do in the past now takes me about two to three weeks” (Weng Kam, 1993). Hence, it is clear from the artist’s statements that, besides low productivity, the eyesight problems affected his colour sensitivity, which might have resulted in the low-quality retouching, as it is an intensive activity that puts a heavy strain on the eyes.

Today, although it is obvious that most of Liu Kang’s retouches are intrusive elements of the paintings, it is challenging to develop a coherent conservation strategy to satisfy conflicting aesthetic and ethical considerations. Despite the arguable quality of the retouching work, the amendments are a legitimate part of the history of the artworks. Regarding the extensively reworked passages of Batik workers (1954), the new colour remains better integrated with the original paint scheme; however, these repairs stand out due to the absence of a filling material.

A review of the ethical guidelines produced by the American Institute of Conservation (AIC) and the Institute of Conservation (ICON) highlighted a few of the most relevant recommendations. The AIC states that: “All actions of the conservation professional must be governed by an informed respect for the cultural property, its unique character and significance, and the people or person who created it” (AIC, 1994). Similarly, the ICON advises conservators to “Act with awareness of and respect for the cultural, historic and spiritual context of objects and structures” (ICON, 2020). Hence, a universal conservation approach is to leave the artist’s additions or alterations intact as artists are often inspired to return to their earlier artworks. Nonetheless, exceptions can be considered if the artist’s restorations and retouches are distracting (Von der Goltz and Stoner Hill, 2012). Despite its subjectivity, such judgement should be made with reference to historical facts (Appelbaum, 2010; Talley, 1996), which, when combined with the technical analyses, may assist in clarifying the intended artistic concept and decisions. Hence, for some of his paintings, the archival sources can reveal the original state of the paint layers and provide information about the possible circumstances behind the retouching process. On the other hand, there is a possibility that the artist was conscious of the inadequacy in his retouching works but fully accepted them as a legitimate and integral constituent of the artistic concept, or he believed that these imperfections were irrelevant to the overall perception of the artworks. Unfortunately, as oil-based retouches inevitably discolour over time, it is impossible to determine the initial colour inaccuracy, which may have been the reason the artist tolerated them at the time of their execution. It also remains unknown if he would accept the hue deviation observed today. Nevertheless, there is no evidence that Liu Kang relished the effects of deterioration of his paintings; on the contrary, the retouches themselves indicate the artist’s intention to reverse some negative processes that occurred in his paintings. Hence, these speculations lead to the conclusion that we may never be able to fully understand the artist’s intentions and that our interpretations may never entirely cover the truth (Van de Wetering, 1996).

As for the treatment, the considered professional standards support the notion that the artist’s interventions should be preserved as long as they do not endanger the original paint. This approach was recommended in the study of John Linnell’s practice of retouching his own paintings. The study accepts Linnell’s retouches as a legitimate part of the compositions that need to be respected but does not recognise these interventions as integral to his artistic process (Sperber, 2017). It is worth noting that Linnell’s retouches are stable and indistinguishable from the original paint layer in visible light; hence, they do not cause aesthetic issues that were observed in Liu Kang’s paintings.

As continued discolouration of Liu Kang’s retouched areas increases the risk of further reduction of the aesthetic properties of the paintings, the considered approach may be to infill and inpaint the retouched areas of very low quality and which cause the most visually damaging effects. On the other hand, the retouched areas that appear convincing or less distracting could be left untreated. This approach adheres to the ethical conservation standard of reversibility and, at the same time, provides a compromise between the preservation of the historic material embedded in the paint layers and respect for the visual integrity of the paintings. The AIC states: “The conservation professional must strive to select methods and materials that, to the best of current knowledge, do not adversely affect cultural property or its future examination, scientific investigation, treatment, or function. […] Such compensation should be reversible and should not falsely modify the known aesthetic, conceptual, and physical characteristics of the cultural property, especially by removing or obscuring original material.” However, if the most conservative solution – leaving all retouches untreated – is the only option, then adequate display labelling should be provided to prevent public misconception about Liu Kang’s painting practice.

Finally, the utmost caution is recommended when confirming or ruling out the authorship of Liu Kang’s retouches. Besides conducting technical analyses of the paintings, checking the state of the paint layers against the archival data and tracing previous conservation treatments may help in ascertaining the original concept and in elucidating the artist’s intentions.

4.2. Alterations

Many Liu Kang’s paintings did not always arise in a linear workflow. His studio practice and extensive visual library comprising sketches and photographs enabled the depiction of the subject to be done in several steps. Furthermore, as part of the creative process, Liu Kang often returned to his paintings to add some minor finishing touches or conduct major alterations of certain parts of the compositions. The alterations reflect the artist’s quest for a satisfactory artistic outcome. However, regardless of their extent, the revisions often affect the visual aspects of the paintings because of the inconsistency between new and old paint application techniques. Additionally, the revisions may hinder the art historical studies about the artist due to misinterpretation of the provenance and dating of his artworks.

Chinese house (1934) is an example of a minor revision of the painting’s composition. The most intriguing area of this painting is the sky. It is characterised by a texture of vigorous brush strokes relating to the underlying dark paint seen in the areas of its high impastos not completely covered with new paint (Figure 3a– d). RTI, transmitted NIR and XRR imaging revealed that, on the right side of the composition, the artist initially painted a massive tree with rich foliage, which he later replaced with the present silhouettes of two young trees (Figure 3e– f).

Liu Kang, Chinese house, 1934, oil on canvas, 64.5 × 50.5 cm (a) and corresponding VIS diffused (b) and VIS raking light (c) details of the sky area showing the texture of vigorous brush strokes relating to the underlying dark paint seen in the areas of its high impasto that are not completely covered with new paint (d). Transmitted NIR (e) and XRR (f) detail images reveal a tree with rich foliage. Gift of the artist’s family. Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

The cases of Climbing the hill (1948) and Bathing in the river (1947) show how the artist’s revisions interfered with the dating and provenance of his artworks. The alteration of the greenery area in the bottom left corner of Climbing the hill (1948) (Figure 2b) obscured the original signature and 1948 date, which were visualised in NIR image and which corroborated with the archival photograph taken by the artist before the intervention. According to an earlier study (Lizun, 2021a), the XRR imaging did not reveal any paint losses in that area that could have prompted that alteration. Moreover, the optical microscopy showed that the additional paint touches were added after the paint surface had dried. It can be speculated that, after the adjustments were done, the painting was probably left unchanged until the preparation for the exhibition in 1993, when the artist re-signed and backdated the work to 1937 as he was not able to recall the actual date of creation of the artwork. Hence, due to incorrect backdating, the landscape was believed to have been created in Shanghai instead of Singapore.

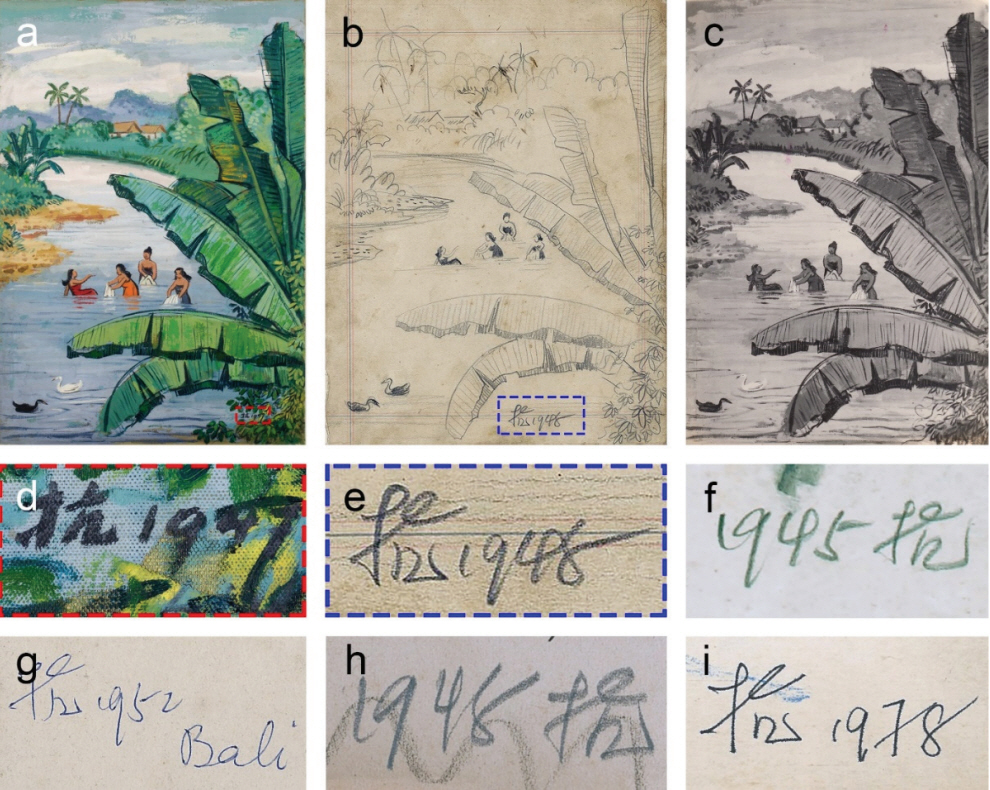

Signed and dated 1947, Bathing in the river (1947) (Figure 4a, d) presents a similar issue, which was clarified by cross-referencing the analytical data with archival sources. The drawing of the composition bears the artist’s signature and date, which could be read as 1945(8) (Figure 4b, e). The ambiguous style of the last digit prompted comparison with other handwritten dates containing the digits “5” and “8” (Figure 4f– i). It was concluded that the artist’s usual style of writing the digit “5” incorporated two strokes – a bulge and a horizontal mark above it. On the other hand, his digit “8” was made in a continuous movement resulting in a loop with either a closed or an open upper part. Hence, the date on the drawing is 1948 and not 1945, suggesting that it was conceived after the painting, which would be an unusual artist’s approach. Interestingly the archival, undated photograph of the painting taken by the artist shows it as unsigned and undated (Figure 4c); therefore, it is conceivable that the artist incorrectly backdated the composition after the archival photograph was taken. Judging from the drawing and photograph, the painting was created in 1948 or later. Moreover, it is assumed that the alterations of the greenery in the bottom-right corner, the shape of the background mountains and upper part of the sky and backdating were executed at the same time (Figure 4a, c).

Liu Kang, Bathing in the river, 1947, oil on canvas, 126.5 × 86.5 cm (a) and corresponding detail showing a signature and 1947 date (d). Gift of the artist’s family. Collection of National Gallery Singapore. Liu Kang, Bathing in the river, 1948, pencil on paper, 27 × 21 cm (b) and corresponding detail showing a signature and 1948 date (e). Undated archival photograph of Bathing in the river by Liu Kang (c). Details showing the: (f) 1945 date and signature from Liu Kang’s drawing of Portrait of a man; (g) signature and 1952 date from Liu Kang’s drawing of Boats from Bali; (h) 1948 date and signature from Liu Kang’s drawing of Brick factory; (i) signature and 1978 date from Liu Kang’s drawing of New Zealand landscape. Images (b, c, e, g–i) are from Liu Kang family collection. Images courtesy of Liu family. Image (f) is a gift of the artist’s family. Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

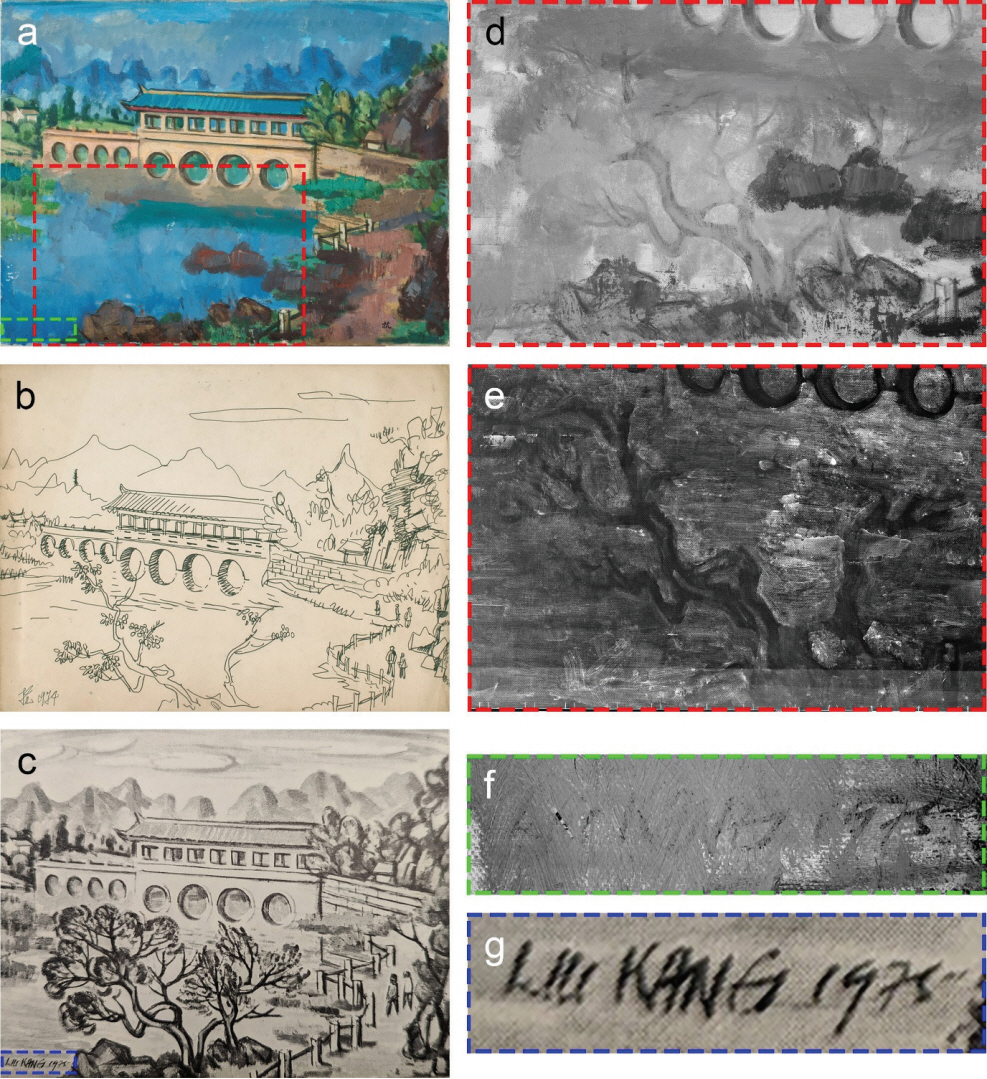

Major alterations by Liu Kang aimed to change the style of the existing compositions. This approach can be illustrated by a signed but undated Chinese bridge over river (Figure 5a). At first glance, the composition strikes the viewer with a stylistic inconsistency. A well-executed bridge in the focal point is surrounded by a roughly expressed lake in the foreground and mountain ranges and sky in the background. Technical analyses coupled with the archival search evidenced some underlying painted features and advanced the interpretation of this artwork. Hence, the roughly painted parts of the composition conceal a brushwork (Figure 5d, e) relating to a signed and dated 1974 preparatory drawing and a signed and dated 1975 painting (Figure 5b, c) presented at the Singapore Art Society 26th Annual Art Exhibition in 1975 (The Singapore Art Society 26th anniversary art exhibition, 1975). Judging from these findings, it is conceivable that, after the exhibition, Liu Kang decided to make a major revision of the foreground and background of the composition by a rough underpainting with local colours, which could serve as a base for further manipulation of the paint with palette knives, followed by detailed brushwork. This resulted in his covering the foregrounded trees, cloudy backgrounded sky and an original signature and 1975 date in the bottom-left corner (Figure 5f, g). Unfortunately, for an unknown reason, he left the work in an apparently unfinished state, judging from the lack of refined foreground details; however, the new signature in the bottom-right corner suggests that he considered his work completed. On the other hand, Liu Kang’s artistic output contains many signed and dated paintings that can be considered unfinished or coloured sketches (Lizun et al., 2021b; Lizun et al., 2022a). Interestingly, the artist, being aware of some inconsistencies in his painting practice, provided an explanation in a 1997 essay: “Though my paintings are guided by a central principle in terms of style, there were some short periods when there would be styles or works that took an entirely different direction from my established style. This was due to the fluctuations of my mood” (Liu, 1997). This revealing statement indicates that emotions impacted Liu Kang’s creative process. Hence, it can be hypothesised that once he lost inspiration or was dissatisfied with the outcome, he was able to abandon the subject or redo it.

Liu Kang, Chinese bridge over river (undated), oil on canvas, 71 × 91.5 cm (a) and corresponding NIR (d) and XRR (e) detail images revealing the painted features of an earlier version of the composition relating to Liu Kang’s preparatory pen drawing on paper, measuring 27.5 × 37 cm, signed and dated 1974 (b). Detail of an NIR image of the painting revealing an earlier signature and a 1975 date (f). Photograph of an earlier version of the painting (c) and corresponding detail showing a signature and 1975 date (g). Painting (a) and drawing (b) are gifts of the artist’s family. Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

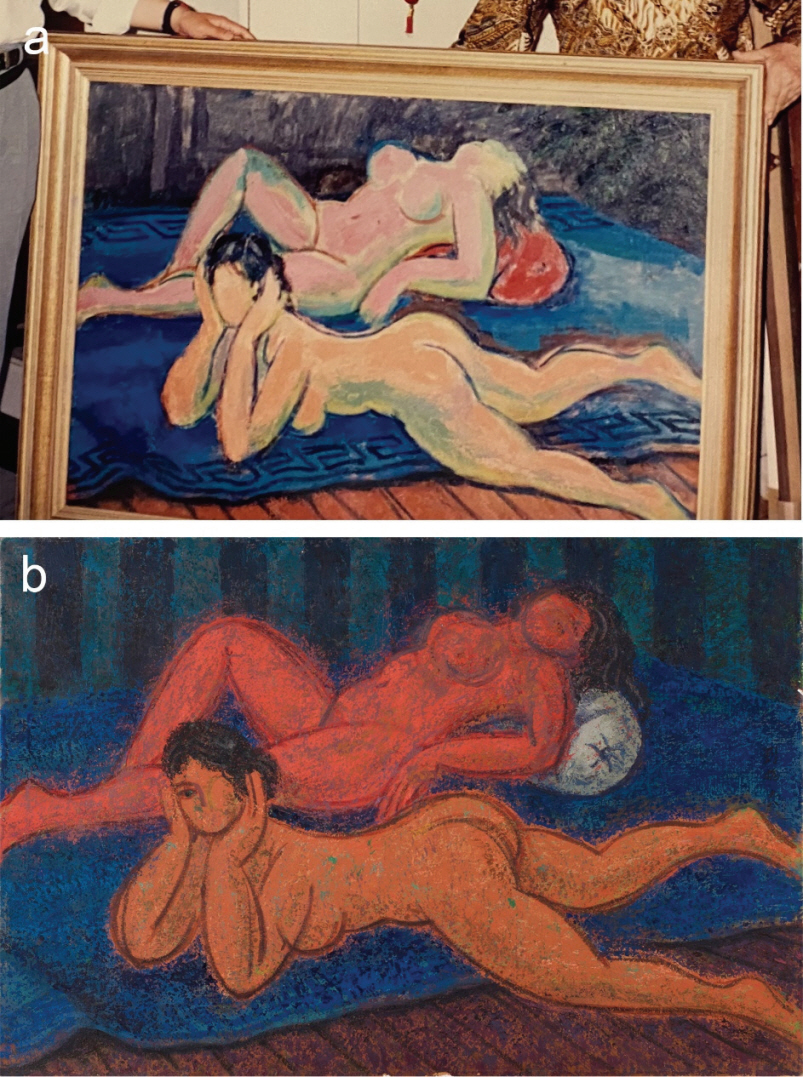

Chinese bridge over river is not an isolated example of a major alteration of the composition, as a similar approach was reported earlier with regard to Beauties at rest II (1998) (Lizun et al., 2022b). The analyses, supported by the archival search, revealed that the first version of the two reclining nudes was probably created in 1993 and repainted in a new style in 1998 (Figure 6). However, it remains unknown what caused a rejection of the earlier version of the painting and the drastic change of the style of its second version. It can only be conjectured that the artist’s decision was either driven by strong artistic self-criticism or inspired by new stylistic concepts.

A 1993 archival photograph of an earlier version of Beauties at rest (a). Liu Kang family collection. Image courtesy of Liu family. Beauties at rest II, 1998, oil on canvas, 85 × 127 cm, painted over earlier version (b). Gift of the artist’s family. Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

Such approach to Chinese bridge over river and Beauties at rest II (1998) bears some resemblance to the case studies of Handsome pork butcher (1935) and Portrait of a doctor (1935) by Francis Picabia, which were altered in a bizarre way due to the death of the subject and an unsuccessful exhibition. Picabia’s reaction to these external circumstances was interpreted as disappointment and anger, which motivated him to reject and rework the paintings in a radical and destructive way to provoke the viewer (King et al., 2018). Although we do not know the circumstances surrounding Liu Kang’s Chinese bridge over river and Beauties at rest II (1998), it is possible that he was disappointed at public reaction to the two artworks and made a radical decision to reject and expressively repaint them.

4.3. Paintings over former compositions

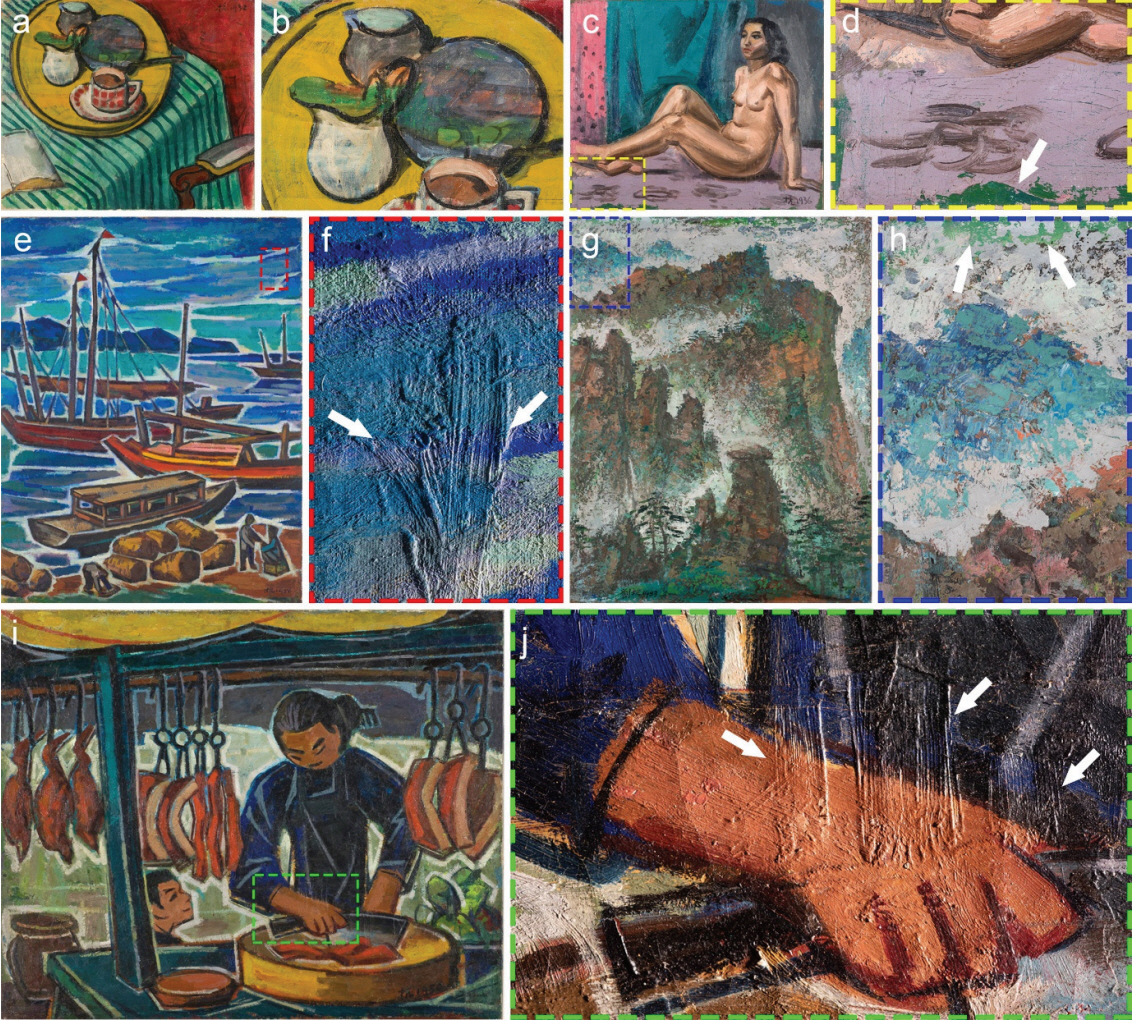

Routine visual examination of Liu Kang’s paintings from his different artistic phases revealed colours and textural irregularities unrelated to the painted subject matter, while DOM enabled the detection of cracks and voids in the surface paint layers, through which different underlying colours are visible. Some of these unusual features blend with the current compositions and remain indiscernible to the average viewer. Other features remain visible and may hamper the perception of Liu Kang’s compositions and colour schemes. For instance, a milk mug from Breakfast (1932) was painted white outside and green inside, whereas a plate is painted with blue, green and orange colours, confusing the viewer about their content or decorative motives (Figure 7a, b). The green and blue patches on the foreground and background of Nude (1936) do not match the main colour scheme of the composition (Figure 7c, d). An unusual paint texture is noticeable on the surfaces of Boats (1956) (Figure 6e, f) and Char Siew seller (1958) (Figure 7i, j). Distinctive green brush strokes are seen on the grey cloudy sky of Mount Huangshan (1983) (Figure 7g, h). Imaging techniques like surface DOM, RTI, NIR and XRR indicated that the visual inconsistency of the paint layers was caused by underlying compositions of the reused painting supports. The artist was not meticulous about hiding former compositions while painting new scenes over them. However, the colouristic and textural incompatibility between the old and new paint schemes seems to point to some randomness in the creative process rather than to the artist’s conscious choice.

Paintings by Liu Kang and corresponding details showing colour and textural irregularities unrelated to the painted subject matter: (a, b) Breakfast, 1932, oil on canvas, 46 × 54 cm; (c, d) Nude, 1936, oil on canvas, 46 × 54.5 cm; (e, f) Boats, 1956, oil on canvas, 91 × 70 cm; (g, h) Mount Huangshan, 1983, oil on board, 84.6 × 64.5 cm; (i, j) Char Siew seller, 1958, oil on canvas, 59.5 × 72.5 cm. Gifts of the artist’s family. Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

With regard to the reasons behind the recycling of the former compositions, the XRR imaging of artworks from Liu Kang’s Paris (1929–1932) and Shanghai (1933–1937) artistic phases did not detect any major ground layer losses that could have encouraged such practice. However, judging from the archival photographs from these periods evidencing Liu Kang’s reuse of auxiliary supports, the artist’s financial constraints could have motivated him to save on art materials and use them creatively (Lizun et al., 2021c). Besides financial difficulties, the scarcity of art materials in post-war Singapore in the late 1940s may have forced him to reach for the old artworks from the Paris and Shanghai phases to paint Climbing the hill and View from St. John’s Fort, both from 1948 (Lizun, 2021a). This radical approach ultimately resulted in the irreparable loss of some completed by signing and dating earlier artworks. In the 1950s and beyond, the artist still considered recycling his paintings as a practical measure. As Liu Kang enjoyed growing professional recognition after the famous Bali exhibition in 1953 (Liu, 1997; Noi and Sin Weng Fong, 1998), it can be hypothesised that his finances improved sufficiently for him to afford the necessary painting materials. Therefore, extensive paint losses of the completed and signed painting of a Balinese dancer created between 1952 and 1958 motivated the artist to reuse the composition for a street scene Char Siew seller (1958) (Lizun et al., 2022a). Another example is In conversation (1999), which has National Art Show exhibition label attached to the back of the canvas (Figure 8a, b). Written in Chinese characters, the information on the label indicates that the title of the artwork is Still life. However, this title and the pronounced brush strokes found across much of the surface do not accord with the current composition (Figure 8c). Further transmitted NIR and XRR imaging techniques confirmed the presence of an underlying still life composition depicting a plant in a flowerpot and a watering can (Figure 8d, e). Interestingly, the label indicated that Still life had initially been earmarked for sale, thus confirming the artist’s confidence in his work at the time of the exhibition. However, the possible unsuccessful sale of the painting could have resulted in its rejection and reuse for In conversation (1999).

Liu Kang, In conversation, 1999, oil on canvas, 61 × 76 cm (a). Exhibition label attached to the back of the canvas (b). Detail VIS raking light (c) and transmitted NIR (d) images of the painting revealing brush strokes of the underlying composition. XRR image of the painting rotated at 90° clockwise, showing a vertical composition depicting a plant in a flowerpot and a watering can (e). Gift of the artist’s family. Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

4.4. Double-sided paintings

Besides overpainting former compositions, Liu Kang utilised the reverse sides of some existing paintings in order to continue the artistic practice despite occasional financial problems and inadequate painting materials. This cost-saving approach reflects his reluctance to overpaint the subject on the main, recto side if it is an artwork that he seemed to have considered satisfactory. All known examples of paintings done on both sides of the same support represent Liu Kang’s early career in Paris (1929–1932) and period of emigration to Malaya (1937–1945). The painting supports were identified as commercially prepared canvases with the primed recto side used first and the verso, raw canvas side used for subsequent paintings. It remains unknown if the artist ranked the paintings on both sides of the support. From subjective assessment, the quality of the paintings on the verso side is in no way inferior to that of the paintings on the recto. Hence, it is likely that both sides were equally important to him. The original framing could have given an insight into the artist’s preference in this matter; however, as such is not existent. One of the investigated double-sided paintings was re-mounted and framed during the artist’s lifetime. Two were restretched after his death, whereas two others remain unstretched.

In this context, Self-portrait (1931) is a rare example of a double-sided canvas painting mounted on a hardboard auxiliary support and framed (Figure 9). The mounting on the hardboard was probably motivated by the poor condition of the tacking margins, which were eventually cut off. Based on the information from the artist’s family, the mounting was done in Singapore by Liu Kang or by a local framer whom he commissioned the framing to. Visual examination revealed that Self-portrait (1931) was executed on the verso of the unknown composition and glued with its recto side to the hardboard. The presence of the paint layer on the main side was visually detected by lifting a corner of the canvas that was detached from the hardboard. As the hidden composition was painted first, it is reasonable to conclude that it was created between the artist’s arrival in Paris (1929) and the execution of Self-portrait on its verso (1931). Although it remains hidden, the XRR could permit its visualisation and assessment of the possible paint losses that could have justified the artist’s decision to discard that composition.

Liu Kang, Self-portrait, 1931, oil on canvas, 55 × 46 cm. The painting was executed on the raw verso side of the unknown composition. Liu Kang family collection. Image courtesy of Liu family.

Double-sided Nude (1940) and Still life (1931) are examples of more complex painting structures, which require careful visual examination backed by knowledge of the artist’s working practice to achieve the correct interpretation (Figure 10a, b). As the artist usually painted on the primed side of the canvas first, the execution of Still life (which is earlier than Nude) on the raw reverse side of the painting support is intriguing (Figure 10c, d). However, the fact that the texture of the brush strokes and exposed colours do not correspond to the final composition of Nude left no doubt about the possible presence of a main underlying scene painted on the primed side of the canvas (Figure 10e, f). Hence, it can be hypothesised that the hidden painting was created in Paris between 1929 and 1931, while Still life (1931) was painted next, on the reverse side. The artist’s decision to recycle the main side of the painting support and overpaint it with Nude (1940) was probably motivated by the poor technical condition of the main composition or the scarcity of painting supports during his emigration to Malaya (Lizun, 2021a). This rare case exemplifies the artist’s unconventional approach to painting supports, which was employed for three compositions.

Double-sided paintings by Liu Kang: (a) recto depicting Nude, 1940, oil on canvas, 38.5 × 46 cm; (b) verso depicting Still life, 1931, oil on canvas, 38.5 × 46 cm. Detail showing the: (c) signature and 1940 date from Nude; (d) signature and 1931 date from Still life; (e) texture and (f) red colour that do not correspond to the final composition of Nude, suggesting the presence of an underlying composition. Liu Kang family collection. Images courtesy of Liu family.

Liu Kang’s double-sided paintings may create conservation and display challenges, especially if alternate or simultaneous viewing is required. In this context, Village scene (1931) and Slope (1931), which are painted on both sides of the same support, are interesting examples (Figure 11). At present, the canvas is temporarily stretched over the strainer and both compositions remain unframed, making them unsuitable for public presentation. The new stretching method may involve a combination of strip lining and a symmetrical strainer or stretcher with key slots on the outside of the bars to allow the display of both the recto and verso image in its entirety (Foulke, 2008; Prins, 2008). As the paintings are oriented horizontally, alternate and simultaneous presentation is possible. However, due to their inversion, a frame rotatable about the horizontal axis can be considered for a visually acceptable display of both sides of the painting support (Runeberg, 2019). As this case is the subject of an ongoing design and fabrication of an auxiliary support and frame to enable future display at NGS, details of the adopted solutions may be discussed in a future publication.

Double-sided paintings by Liu Kang: (a) recto depicting Village scene, 1931, oil on canvas, 46 × 55 cm; (b) verso rotated at 180° depicting Slope, 1931, oil on canvas, 46 × 55 cm. Gift of the artist’s family. Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

Nevertheless, the ultimate recommendation for the future protection of Liu Kang’s double-sided paintings is to avoid ranking the recto and verso compositions, which may lead to preferential framing of one side and negligence and deterioration of the other side. Considering both sides of the painting support as equal enables the viewer to appreciate one or the other side while acknowledging the co-presence of two images. Such an approach will also shed light on the complex nature of Liu Kang’s practice and, in particular, the motivation behind his recycling the verso sides of completed paintings (De Chassey, 2015).

4.5. Relation between the recycled painting supports and the painting techniques of new compositions

The artist’s choice to reuse earlier compositions sometimes determined his painting technique for executing new painted scenes. For instance, Waterfall (1936), Seaside (1936) (Figure 12a, b) and Climbing the hill (1948) (Figure 2b) were created over former, unknown artworks (Figure 12c, d), and the creative process for new paintings involved the extensive use of palette knives followed by florid brushwork (Figure 12e, f) (Lizun, 2021a). A similar approach was observed in executing the special theme of Huangshan and Guilin mountains in the 1980s and 1990s. These paintings were largely created over reused compositions on hardboard. Palette knives were employed for a quick and effortless covering of rejected scenes with new paint and for developing the new compositions.

The paintings by Liu Kang: (a) Waterfall, 1936, oil on canvas, 65 × 50.3 cm; (b) Seaside, 1936, oil on canvas, 45 × 54 cm. Corresponding XRR (c) and NIR (d) images showing illegible underlying compositions. Detail of Waterfall (e) and Seaside (f) indicating palette knife paint application followed by detailed brushwork. Gifts of the artist’s family. Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

Judging from the undated archival photograph documenting the transition from the earlier to present version of Beauties at rest II (1998), a broad and flat application of the local colours with brushes was required for the quick underpainting (Figure 13). As the artist intended to work within the existing composition, the choice of brushes for the underpainting seems adequate as they provided better control of the paint application around the shapes he wanted to reuse. Further development of the scene involved palette knives for hiding the remains of the rejected paint scheme and producing a base for the manipulation of the colours with brushes (Lizun et al., 2022b).

An undated archival photograph showing Beauties at rest during the transition from an earlier to the present version of the composition (a). Liu Kang Collection, National Library Singapore. Beauties at rest II, 1998, oil on canvas, 85 × 127 cm, the final version of the painting (b). Gift of the artist’s family. Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

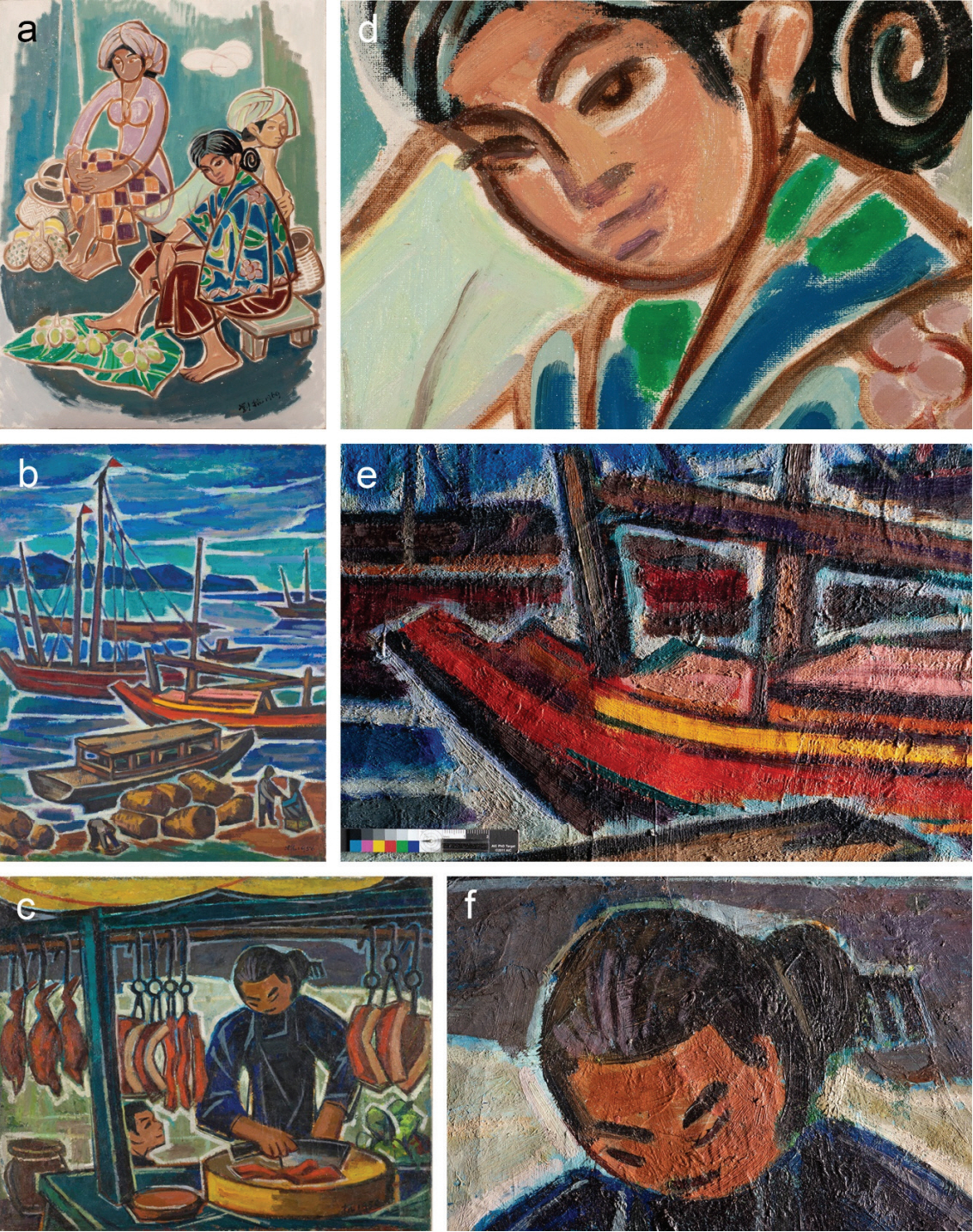

Nevertheless, the most significant impact of the recycled compositions on the adopted painting technique and the artistic outcome of the new paintings can be observed in Boats (1956) and Char Siew seller (1958). Both artworks were executed in the batik-inspired painting technique characteristic of Liu Kang’s Nanyang-style paintings. Their technical principle was an intentional exposure of white ground for enhancing the shapes of the compositional elements and increasing their colour contrast as can be seen in Fruit sellers (1969). The colour effects were based on simple tonality, and the paint was applied confidently with brushes, producing minimal texture (Figure 14a, d) (Lizun et al., 2022a). Hence, a painting support with a white ground layer was crucial for achieving these optical effects. As Boats (1956) and Char Siew seller (1958) were executed over earlier compositions, the white ground layer was unavailable. Hence, it had to be substituted with white paint applied in the final stage of the creative process to delineate the forms. This approach produced a lower contrast between the colours mainly due to the contamination of the white paint with other colours present on the palette and painting. Moreover, the act of painting over the earlier compositions produced tonal transitions and rich texture – radically different features from typical Liu Kang’s batik-inspired technical solution (Figure 14b– f). The identification of these unusual technical features on his batik-inspired paintings may indicate the artist’s departure from applying a pure Nanyang style, motivated by the limitations of the painting support. It may also tentatively signal the presence of the underlying compositions.

Paintings by Liu Kang: (a) Fruit sellers, 1969, oil on canvas, 122 × 91.5 cm; (b) Boats, 1956, oil on canvas, 91 × 70 cm; (c) Char Siew seller, 1958, oil on canvas, 59.5 × 72.5 cm. Gifts of the artist’s family. Collection of National Gallery Singapore. The corresponding detail images show features of the original batik-inspired painting technique with a white ground exposed (d) and substituted colour of ground with a white paint applied in the final stage (e, f).

5. CONCLUSIONS

The collaborative endeavour entailing technical imaging and archival research allowed to identify and categorise some intriguing technical features of Liu Kang’s paintings, which define the less known and mysterious side of his oeuvre.

The presence of compositional or colouristic alterations may either reflect the artist striving to achieve satisfactory artistic outcomes or indecision despite his having conducted extensive studies of the subject matter through drawing and photography. Nevertheless, the studies of Liu Kang’s painting alterations may add to the knowledge about the artist’s development of individual compositions from conception of the idea to execution. An important point of the discussion is that the alterations were sometimes carried over the initial signatures and dates, and subsequent re-signing and backdating do not accord with the factual creation of the artwork or its revision. Cross-referencing the technical analyses with the archival sources seems to be an adequate approach to resolving ambiguous cases.

The artist often reused painting supports for new compositions, created either on the recto or verso side of his earlier artworks. However, there were different reasons behind these decisions. During the period from the 1930s, which marks the beginning of his career in France, to the late 1940s, before he became a well-known artist, the decision to paint over earlier compositions was often caused by financial constraints and the non-availability of art materials. In the case of rare double-sided paintings, the material evidence suggests that they are typical of his early career in Paris (1929–1932) and period of emigration to Malaya (1937–1945), and they are the result of saving on painting supports while preserving the recto side from overpainting. The discovery of the underlying compositions in paintings from his successful, mature years (1950s–1990s) points more to the practical aspect of utilising rejected artworks than an extreme cost-saving solution. Hence, extensive losses to the paint layer might have been another reason for his overpainting the original composition of a Balinese dancer with Char Siew seller (1958). However, if the composition presented itself as valuable to the artist, he was inclined to retouch even the extensive paint losses as is the case of Batik workers (1954). The emotional reactions to the external circumstances surrounding Chinese bridge over river and Beauties at rest II (1998) are also considered as potential causes of the radical reworking of these paintings.

The study highlighted the correlation between Liu Kang’s recycling of painting supports and the painting technique he adopted for new compositions that were created over earlier artworks. Moreover, it demonstrates how recycled painting supports may determine the primary or secondary quality of Liu Kang’s batik-inspired paintings.

As for the conservation and display considerations, special attention is particularly necessary for assessing his writing character and the authorship of retouches and alterations. This can reduce the risk of incorrect dating and unintentional removal or cover of the original material. Furthermore, the study took an opportunity to overview the ethical and aesthetical considerations in the context of potential treatment of Liu Kang’s low-quality and discoloured retouches. The artist’s approach to paintings on the reverse sides of earlier compositions was discussed. The study traced the intricate painting sequence of two double-sided artworks and highlighted potential stretching and framing challenges of the double-sided Village scene and Slope, both from 1931. However, the detailed approach to alternate or simultaneous presentation of Liu Kang’s double-sided paintings was beyond the scope of the current research and will be addressed in the next phase. Finally, the highlighted aspects of Liu Kang’s creative process may raise the awareness of the complexity of his unconventional approach to painting among the conservator, art historians and the public, and encourage further research in this field.

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out through the support of the National Gallery Singapore and Heritage Conservation Centre in Singapore. The authors are thankful to Gretchen Liu for allowing access to the Liu family collection and the artist’s archives and Kenneth Yeo Chye Whatt (Principal Radiographer from the Division of Radiological Sciences at Singapore General Hospital) for facilitating the X-ray radiography. The authors wish to thank reviewers for their comments, which were essential for making improvements to the manuscript. This article is a part of the ongoing PhD research of the first author supported by the Nicolaus Copernicus University. The research focuses on the painting materials and working practice of the important Singapore artist Liu Kang.